Alvàpurrinu's grammar was mostly completed back in 2017. There are a couple of sections that will no doubt require some rework, but I had a much clearer idea of what I wanted this conlang to be than I did with Dauvonic. It shouldn't take too long to clean up. I might actually be done with it by the end of the month.

Alvàpurrinu's grammar was mostly completed back in 2017. There are a couple of sections that will no doubt require some rework, but I had a much clearer idea of what I wanted this conlang to be than I did with Dauvonic. It shouldn't take too long to clean up. I might actually be done with it by the end of the month.

Remember how I said at the beginning of June that I'd like to revise at least one of my old conlangs per month? I didn't get around to that in June, mostly because I was working on fleshing out A̋llunóñe. But in the past few days, I've actually taken the time to look at some of those old conlangs, and I've picked the one that I'll be working on this month – and, most likely, the next few months. I don't know why I thought I could get one of them cleaned up per month, especially since most of them aren't even "complete".

The conlang that I've decided to focus on cleaning up for the time being is one I created in 2015. After all this time, it doesn't even have a real name – I've been calling it either Tonal Celtic or Dauvonic. It was originally envisioned as a Celtic language with tones like Mandarin Chinese, but I'm not quite sure I want to do that anymore.

I remember not wanting the language to have initial consonant mutations, but I don't remember why – possibly because Dauvonic is supposed to be a continental Celtic language similar to Gaulish, and

Gaulish never had any evidence of initial consonant mutations. I'm thinking now that I do want Dauvonic to have them, mostly because I'm not sure what to do with this conlang's case system.

I have a lot of decisions to make on a conlang that was only ever one-third finished nine or so years ago. I'll probably make updates as I get through things, just like I've been doing with A̋llunóñe.

Eventually, I'll be sharing this information online, just like with my other conlangs. On Dreamwidth, I have one post per conlang, and that worked just fine. But I don't think it will for A̋llunóñe. The documentation is already at 19 pages, and there are plenty of sections of the grammar I haven't even touched yet. I don't even have word order yet.

I'll definitely have to make multiple blog posts, but I haven't yet decided how many. Or maybe I'll just make one blog post, with the information condensed down to the most important things.

I spent some time working on my conlang this weekend, and it's finally got a name: a̋llunóñe, which is pronounced [ˈaː.lːu.ˌnoː.ɲe]. I wanted a name that would show some of the diacritics the conlang's orthography uses, and this one has three! It's a little hard to type since <a̋> isn't part of the US-International keyboard layout I use; I have to copy-paste it.

All my previous conlang posts relating to this language have been tagged allunone, for ease of finding information.

After deciding that syllables could end in /t/, I decided to remove that rule. I only had two words will syllables ending in /t/ and I didn't actually like how they looked.

I took the time to work on adjectives and verbs this past week. I decided that adjectives precede nouns, agree in case and number, and are declined like nouns – so they have different declensions depending on if they end in a vowel or consonant. I also worked out comparative and superlative forms of adjectives.

For verbs, I decided they'd be marked for tense and mood. I originally wanted them to be marked for person and number, but then I decided there would be four different verb conjugations, and since this is a fusional language and not agglutinative, I'd have to create way too many verb endings if I marked person and number as well.

Yes, four verb conjugations. There's a conjugation for verbs ending in vowels, one for verbs ending in nasals, one for verbs ending in /s/, and one for verbs ending in approximants. I could have had separate vowel and consonant conjugations like with nouns, but I thought that would be too boring.

The thing I'll be working on next is the pronouns system, which will probably end up being fairly complicated as the culture attached to this conlang has a pretty strict caste system. After that, it's on to numerals.

In early 2021, I created a goal to clean up my conlangs. At the time, I had about two dozen conlangs in various stages of completion. I had no consistent templates for grammars or dictionaries, so information for one conlang may have been easy to find while information for another may have been all over the place.

For about five and a half months, I worked diligently on standardizing the way I kept information on my conlangs. I got through about half of them and then…stopped, for some reason. I don't remember why. The results of that conlang cleanup can be seen on my website, or in this tag here on Dreamwidth.

A couple of days ago, I looked in my conlangs folder and found out that there are some conlangs there that I had completely forgotten about. One of them hadn't been touched since 2017. That one in particular I thought I had already deleted.

Clearly I need to finish the cleanup I started in 2021. I think I'll aim for one conlang per month. That should be easy enough to accomplish. And who knows – maybe I'll have blog posts online about those conlangs in a few months.

I have a potential name: tukaññe, which doesn’t mean anything in the conlang. I'm not too satisfied with it and will probably come up with something else that actually means something and doesn't look too much like "toucan".

I've added a lot of words – mostly nouns, but also some adjectives and verbs. I've even created two prefixes and one suffix!

I've decided that syllables can also end in /s r l t/, mostly because I wanted more variety in syllables. Also, I apparently ignored my own rule about front vowels only existing where /i/ or /y/ in the following syllable causes a back vowel to front, so I'm dropping that. It clearly wasn't that important if I forgot about it.

I have changed the orthography slightly. /ɕ/ now represented by <š>.

I'm still not sure how to mark animacy. Maybe I'll end up with no noun class system at all.

I have not worked on adjective or verb forms yet. I know what I want verbs to mark, but I haven't created the declensions yet. I haven't even decided on the number of declensions I want to have.

One of the first decisions I made was to have the phonology be sonorant-heavy. From there, I decided that there would be a full "set" of palatal consonants. That led to all consonants being able to be palatalized, which then led to all back vowels having corresponding front versions.

Here is the current consonant inventory. Consonants in parentheses are exclusively palatalized versions of other consonants: [c], [ç], and [ʎ] are the palatal versions of /k/, /h/, and /l/.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ |

| Stop | p | t | (c) | k |

| Affricate | ts | tɕ | ||

| Fricative | s | ɕ (ç) | x | |

| Approximant | w | l ɹ | j (ʎ) |

There are no voiced stops solely because it didn't fit the aesthetic I had in mind for the conlang. As for the orthography, the only consonants that don't match their IPA values are /ɲ/, /ŋ/, /ɕ/, /x/, and /j/, which are written <ñ>, <ng>, <sh>, <h>, and <y>, respectively.

For vowels, I didn't really know what I wanted except for /i/, /e/, and /a/. I then expanded that to include /o/ and /u/, but still didn't know how to make the vowel inventory unique. It didn't necessarily need to be unique, but I didn't exactly want to go with the "standard" vowel phonology. That seemed a bit boring.

I decided that back vowels would front when the following syllable contained a front vowel. Now there were five front vowels and three back vowels. Then, because that wasn't enough, I decided to add vowel length. The current vowel inventory is shown below.

| Front | Back | |

| Close | i iː y yː | u uː |

| Mid | e eː ø øː | o oː |

| Open | a aː | ɑ ɑː |

The vowels /y/, /ø/, and /a/ are written <ü>, <ö>, and <ä>. Long vowels are indicated with an acute accent. For the "regular" vowels, this produces <á>, <é>, <í>, <ó>, and <ú>. I was a little confused as to what to do with <ü>, <ö>, and <ä>, until I did some research and found out that double acute accents exist – Hungarian uses them, among other languages. So the long versions of <ü>, <ö>, and <ä> are <ű>, <ő> and <a̋>.

That's about it for the phonology at the moment. I haven't really decided on the stress system or if I want any diphthongs to exist.

For grammar, I've just started working on nouns. I knew from the beginning that I wanted at least two unique noun classes – I decided on animate and inanimate – but not much else. What would nouns be declined for? Are those declensions suffixes or postpositions? What kind of agreement do they have with other parts of speech?

I decided that this language wouldn't be agglutinative. Most of my conlangs are, because it makes things nice, orderly, and easy to remember. But I wanted this conlang to look like a language with a long literary history – my initial inspirations were Tocharian and Sanskrit – so I decided it would be fusional in morphology.

This isn't a very big deal at the moment, since nouns are only declined for case (nominative, genitive, accusative, dative, and vocative) and number (singular and plural). Animacy isn't distinguished on nouns; it will be instead shown on some other part of speech – I haven't yet decided if it will be articles, prepositions, adjectives, or something else.

Since words can end in either vowels or certain consonants, I made different declensions for vowel-final nouns and consonant-final nouns. There are two examples below.

Declension of süriññe "temple" (vowel-final declension):

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | süriññe | süriññel |

| Genitive | süriññes | süriññem |

| Accusative | süriññele | süriññen |

| Dative | süriññeha | süriññer |

| Vocative | süriñña̋ | süriññő |

Declension of pekweñ "book" (consonant-final declension):

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | pekweñ | pekweññe |

| Genitive | pekweñña | pekweñaru |

| Accusative | pekweññé | pekweñelu |

| Dative | pekweññi | pekweñäye |

| Vocative | pekweñám | pekweñámu |

Süriññe and pekweñ are actually the only two words I've created. I don't even have a name for this conlang yet!

I may or may not make more update posts on this conlang. If I do, I doubt it'll be on any sort of regular schedule.

The problem – aside from not really having the time to work on a conlang with all the other things I've got going on right now – is that I have no idea what kind of conlang I want to make. Do I want to revamp one of my old, abandoned conlangs into something usable? Do I want to create something entirely new from scratch? Do I want to create a descendant of Tocharian B? Do I want to create the conlang that will be used in the story I've recently come up with?

I have a lot of decisions to make even before I get to the stage where I start writing things down.

Introduction

Rennukat, meaning "moon language", is the majority language spoken in Tsurennupaiva, "The land of two moons". There is one major divergent dialect, Aven ferkat "Aven dialect", spoken by people from the area in and around the town of The Avens in the Western District. The difference is roughly the same as the differences between Scots & English. This is the dialect that Kallinu Jurne speaks.

I started working on Rennukat in June 2018 - the same time I started working on The Land of Two Moons. There are some minor influences from Japanese & Finnish, primarily in the phonology, grammar, and pronouns.

Phonology

Consonants

The consonants /b/, /g/, /z/, and /θ/ only occur in old loanwords from other languages. I spent a very long time thinking if I wanted to include those consonants at all, since they really didn't fit with the feel that I was going for.

But Rennukat is supposed to be a naturalistic language, and natlangs adopt consonants and vowels (and word spellings) from other languages all the time, so I kept them in.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

| Nasal | m | n | |||

| Stop | p (b) | t d | k (g) | ||

| Fricative | f v | s (z) ʃ (θ) | h | ||

| Affricate | tʃ ts | ||||

| Approximant | r l | j |

Vowels

Rennukat's vowels system is (with the addition of a few vowels) the standard vowel system I had in most of my earlier conlangs: a short/long distinction for the front and back vowels, and two central vowels: /ə/ and /a/. Short vowels occur when there is a consonant in the coda, and long vowels occur when there is no following consonant in the coda.

[æ], [ɑ], and [ə] are all allophones of /a/, because Rennukat absorbed a lot of words and pronunciations from other languages and it seemed more natural to have some random variations.

| Front | Central | Back | |

| Close | ɪ ʏ i y | ʊ o | |

| Mid | ɛ e | (ə) | ɔ o |

| Open | (æ) | a | (ɑ) |

Rennukat has a couple of diphthongs: /aɪ/, /aʊ/, /eɪ/, /oɪ/, /oʊ/. Like with the monophthong vowels, they're also part of my standard phonology from my early conlanging years.

Syllable Structure & Consonant Clusters

Rennukat's syllable strucure is CVF, where C is any consonant, V is any vowel or diphthong, and F is any alveolar EXCEPT affricates and /ʃ/.

Consonant clusters only occur mid-word. Any loanword that appears to have a consonant cluster at the end of a word is not pronounced that way. I don't actually have any examples of this.

All alveolars can technically be geminated, but in practice, only /n/, /s/, /r/, and /l/ are geminated. In a couple of dialects, /ss/ becomes /ʃ/, /ʃʃ/, or /sʃ/.

Sentence Structure

Rennukat's word order is Subject-Object-Verb. Pronouns (often the subject of the sentence) are dropped unless absolutely necessary. The subject of the sentence is dropped in subordinate clauses.

Examples of simple sentences:

Hallion tyvosa.

- The sun is shining.

- Sun.NOM shine.PRS

Joilla mei iro.

- I think, therefore I am.

- Think.PRS.IND so exist.PRS.IND

Rennukaticha mousso.

- I speak Rennukat.

- Rennukat.ACC speak.PRS.IND

Rennukat has no dummy pronouns; there's no equivalent of "it" in sentences like "it's raining" or "it's sunny outside":

Henosa.

- It's raining.

- Rain.PRS

Questions

The verb in a question takes the subjunctive mood.

"What" questions are formulated in the same way as a normal sentence, just with the question word at the beginning.

- What: kehtu

- Where: ke'givvra

- How: ke'vemy

- Who: k'ollin

- Why: ke'jyhteit

- When: k'otinne

Kehtu maita kehtosatur?

- What is magic?

- What magic.NOM be.PRS.SBJ

Ke'givrra kala irosatur?

- Where is the lake?

- Where lake.NOM exist.PRS.SBJ

Ke'vemy toricha nirairuur?

- How did you build the house?

- How house.ACC build.PST.SBJ

K'ollin de toricha nirairutur?

- Who built this house?

- Who PROX house.ACC build.PST.SBJ

Ke'jyhteit juechat kivrasatur?

- Why do you have fish?

- Why fish.ACC.PL have.PST.SBJ

K'otinne vuhtacha akoisatur?

- When did you see the ghost?

- When ghost.ACC see.PST.SBJ

Yes/No questions must start with the question particle larai. As there are no words for "yes" and "no", the verb must be repeated with negation or affirmation if necessary.

Larai henosatur?

- Is it raining (right now)?

- QP rain.PRS.SBJ

Henosa tou.

- Yes, it's raining.

- rain.PRS.IND affirmative

Henosa nas.

- No, it isn't raining.

- Rain.PRS.IND negative

Nouns & Adjectives

Nouns are marked for six cases and two numbers. Adjectives precede nouns, and must agree in case and number.

Rennukat has fewer locative cases than a few of my other conlangs. I didn't want it to have too many, since that would make it a little too similar to Finnish.

| Case | Singular | Plural |

| Nominative | - | -(i)t |

| Accusative | -(i)cha | -(i)chat |

| Genitive | -o | -ot |

| Dative | -(i)lla | -(i)llat |

| Ablative | -(i)hty | -(i)htyt |

| Allative | -(i)nne | -(i)nnet |

Pronouns

Rennukat has a lot of pronouns. There are five 1st-person pronouns, three 2nd-person pronouns, and three 3rd-person pronouns. I didn't want to put gender on the 3rd-person pronouns, so decided that some of the 1st-person pronouns would be gendered instead - much like what Japanese does.

All pronouns have rather irregular declensions when compared to other nouns.

1st Person Pronouns

There are two sets of 1st-person pronouns: casual and formal. Casual pronouns are used in casual and informal settings, and formal pronouns are used in formal settings and by professionals such as teachers, civil servants, & people in the military.

The most commonly used casual pronouns are the gendered ones. The plural forms of gendered pronouns mean "we men", "we women", "we agender people" rather than referring to a group that one is part of - the general casual plural is used for that.

The male casual pronoun is ohu, which is a contraction of de bohku "this man". It is often shortened even further into o'u /oʊ/ in the nominative.

The female casual pronoun is ein, a contraction of de eillin or d'eillin "this woman". An earlier form was d'ein.

The agender casual pronoun is dyrru, which is a contraction of de kyrru "this agender person".

The general casual pronoun is minno. It is less informal than the gendered pronouns, but less formal than the 1st-person formal pronoun.

Minno and arre are the original 1st-person pronouns. The gendered ones came later.

2nd Person Pronouns

There are three distinct 2nd-person pronouns: informal/subordinate, formal/superior, and general/peer.

The informal/subordinate pronoun, jassu, is used when addressing subordinates and people younger than the speaker. It is used by teachers speaking to their students, professionals speaking to their clients, parents speaking to their children, people in the military speaking to civilians, and the Avatar when addressing anyone.

The formal pronoun, fynne, is used when addressing superiors and people older than the speaker. It is used by students addressing teachers, people speaking to hired professionals (doctors, lawyers, plumbers, etc), children speaking to their parents, civilians speaking to people in the military, and anyone speaking to the Avatar.

3rd Person Pronouns

Third person "pronouns" consist of a demonstrative followed by ollin "person". It is possible to use gendered words such as bohku, eillin, and kyrru, but the use is discouraged as it is considered rude. The contracted forms of the demonstratives de, no, and tau, (d', n', and t') are used unless the speaker wants to be exceptionally formal.

D'ollin, meaning "this person, close to me", is used when the speaker is talking about a person close to them.

N'ollin, meaning "that person, close to you", is used when the speaker is talking about a person close by to the person they are speaking to.

T'ollin, meaning "yonder person, far away from both of us", is used when the speaker is talking about a person that is far away from everyone involved in the conversation.

Demonstratives

Rennukat has three demonstratives: a proximal, medial, and distal.

- Proximal: de

- Medial: no

- Distal: tau

Verbs

Verbs are marked for tense, mood, voice, and affirmation/negation. Since Rennukat is primarily an agglutinative language, this happens in the form STEM-TENSE-MOOD-VOICE.

All verb stems end in -a, -o, -ai, or -oi. I considered removing those endings when adding on the tense/mood/voice suffixes, but then decided against it for a reason I genuinely can't remember.

Tense

Verbs have three tenses: past, present, and future. The past tense ending is -ru, which comes from the noun runo meaning "(the) past". The present tense ending is -sa, from the noun sain meaning "(the) present (day)", and the future tense ending is -yt, from the noun yhtor meaning "(the) future".

I'm not 100% certain on this, but I don't think most languages take their verb tenses from temporal nouns - those things seem to be separate. The way I constructed things here would seem to insinuate that those things were deliberately created at some time in the past.

Since Tsurennupaiva's culture was deliberately crafted in the past, it wouldn't be too difficult to imagine that this also happened with some aspects of Rennukat.

Mood

There are five moods: indicative, subjunctive, conditional, optative, and imperative.

The indicative is used to express factual statements. It's the "default" mood, and so has no suffix.

The subjunctive is used to express theoretical and unconfirmed statements, as well as ask questions. The suffix is -(t)ur. It was originally just -ur, but that created some words that looked too weird for my liking.

The conditional is used to express than an action is dependent on some kind of condition. The suffix is -mel.

The optative is used to express hopes, wishes, and prayers. The suffix is -ty, from tyle "wish".

The imperative is used to express orders. The suffix is -ko.

Voice

Rennukat's verbs have two voices: active and passive. The active voice is the default, and is unmarked. The passive ending is -(e)s. I originally thought this resembled English verbs a little too much, but in practice, they don't look English at all:

- nirai "to build" vs. nirais "to be built"

- rahkasa "falling" vs rahkasus "to be falling"

Affirmation & Negation

As mentioned in the previous section about sentence structure, Rennukat has no words for "yes" or "no". There are, instead, particles for negation (nas) or affirmation (tou) that follow the verb. Nas is used to answer a question or form a statement in the negative. Tou is used more rarely, since the existence or occurrence of things is assumed by default.

Henosa.

- rain.IND.PRS

- It is raining.

Henosa tou.

- rain.IND.PRS AFFIRMATION

- Yes, it's raining.

Henosa nas.

- rain.IND.PRS NEGATION

- No, it's not raining.

Numbers

Rennukat has a rather boring decimal number system. There are unique numbers for 0, 1-10, 100, and 1000. Multiples of ten are formed by a numeral from 2-9 followed by nyt. Multiples of 100 and 1000 are formed in a similar way.

Here are some random numbers:

- 27: tsu nyt mortu

- twenty-seven

- 108: rassein sahtai

- (one) hundred eight

- 499: ehta rassein shin nyt shin

- four hundred ninety-nine

- 1034: yrtenys lare nyt ehta

- (one) thousand thirty-four

- 54,321: keir nyt ehta yrtenys lare rassein tsu nyt yhdi

- fifty-four thousand, three hundred, twenty-one

Introduction

Askeisk is a North Germanic conlang. It belongs to the West Scandinavian branch and is spoken on the (fictional) island of Askei, located halfway between Shetland and the Faroe Islands. It has around 5,000 speakers, many of whom are also bilingual in either Irish, Icelandic, or Norwegian.

Askeisk was primarily created for a story I was thinking about writing in 2016. That story is permanently on hold, but the conlang has managed to hold my interest for quite a long time.

Phonology

Askeisk's consonants are fairly similar to the other North Germanic languages. At one point, it included /ɬ/, /ð/, and /θ/, but I removed them as I didn't want to deal with too many fricatives. Like in Faroese and Iceland, stops contrast aspiration instead of voicing.

Askeisk's vowels are thoroughly uninteresting. Each vowel is either long or short. Short vowels exist in closed syllables (end with a consonant) and long vowels appear elsewhere.

Consonants

- Nasals: m n ɳ ɲ ŋ

- Stops: pʰ p tʰ t ʈʰ ʈ cʰ c kʰ k ʔ

- Fricatives: f v s ʃ ʂ ç h

- Approximants: l ɹ ɭ ɻ j

Certain consonants & consonant clusters have "soft" (palatalized) versions which only occur before front vowels. I created this rule before I decided on an aspiration rather than voicing distinction, which is really the only reason /g/ becomes [j] and not [c]:

- /k/ → [c]

- /g/ → [j]

- /h/ → [ç]

- /n/ → [ɲ]

- /sk/ → [ʃ]

Certain consonants followed by /j/ become palatalized:

- /nj/ → [ɲ]

- /hj/→ [ç]

- /gj/ → [j]

- /kj/ → [c]

- /tj/→ [ʃ]

- /sj/ → [ʃ]

All geminated, nonaspirated stops become preglottalized:

- /gg/ → [ʔk]

- /bb/ → [ʔp]

- /dd/ → [ʔt]

Meanwhile, geminated, aspirated stops become preaspirated:

- /kk/ → [hk]

- /pp/ → [hp]

- /tt/ → [ht]

Other misc sound changes:

- /nn/ → /tn/ → [ʔn̩]

- /ll/ → /tl/ →[ʔl̩]

- /gl/ → [ll]

- /skj/ → [ʃ]

Vowels

- Close: iː yː uː ɪ ʏ ʊ

- Mid: eː øː oː ɛ œ ɔ

- Open: æ æː a aː

At one point, every first-syllable /a/ was [æ]. I then decided that was obnoxious and made /æ/ its own independent phoneme.

There are quite a few possible diphthongs, but not all of them occur in actual words:

- aɪ aiː aʊ auː

- ɛɪ eiː

- ɔɪ oiː ɔʊ ouː

- œʏ øyː

- ʊɪ uiː

Stress

Like Norwegian and Swedish, Askeisk has a pitch accent! I guess at some point I decided I needed some kind of difference from Faroese and Icelandic, because I absolutely remember there being a stress system initially.

Monosyllables have no accent. Bisyllabic or longer words are pronounced with a rising tone on the first syllable.

Syllable Structure & Consonant Clusters

Askeisk's orthography isn't particularly strange, I think.

I'm including diphthongs & digraphs here because why not?

Orthography

Grammar

Askeisk's grammar is pretty straightforward North Germanic. I did consider adding in some Irish influences, including some kind of initial consonant mutation, but I genuinely could not figure out how to make it work.

Nouns

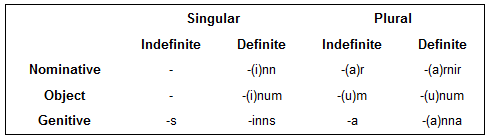

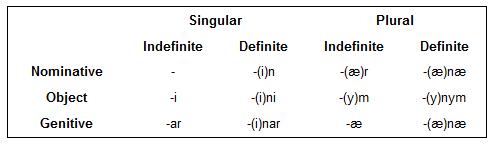

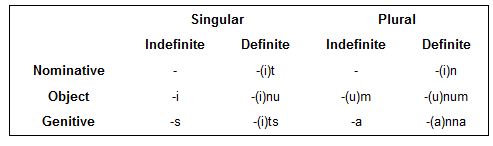

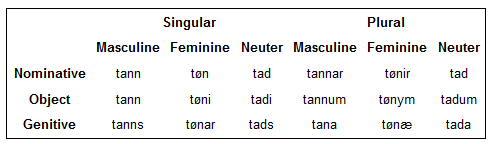

Nouns have three cases (nominative, object, and genitive), two numbers (singular and plural) and three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter).

The object case comes from the merger of the dative & accusative cases. For the most part, the object case declensions descend from the Old Norse dative declensions.

Nouns - Masculine

The masculine noun declension is basically identical to that of Old Norse:

Examples:

- fadir "father" → fadrinn, fedrar, fedrarnir

- hund "dog" → hundinn, hundar, hundarnir

- mauni "moon" → mauninn, maunir, maunarnir

- ørn "eagle" → ørninn, ernar, ernarnir

Nouns - Feminine

The masculine and feminine declensions were too similar at first. I spent a while thinking about how to distinguish them instead of collapsing them both into common like Danish and Swedish, and came up with something I think is fairly unique.

The plural declension of feminine nouns exclusively contain front vowels. This causes /u/, /o/, & /ou/ to front to /y/, /ø/, and /øy/. I took this from what happens to the feminine forms of adjectives, which is something I came up with long before I decided to do this.

Many other random back vowels get fronted, but...it's random. I don't think I decided on an actual pattern for it.

Examples:

- aska "ash" → askan, askær, askænæ

- douttir "daughter" → douttrin, døyttrær, døyttrænæ

- gaus "goose" → gausin, gæysær, gæysænæ

- ull "wool" → ullin, yllær, yllænæ

Nouns - Neuter

Neuter nouns are the same in the nominative plural and singular (except for some occasional vowel changes). I did nothing interesting with this declension.

Examples:

- barn "child" → barnit, børn, børnin

- egg "egg" → eggit, egg, eggin

- hus "house" → husit, hus, husin

- navn "name" → navnit, nøvn, navnin

Personal Pronouns

Askeisk's personal pronouns are nothing special. There are singular and plural versions, three genders in the third person, and possessive pronouns have different forms depending on the gender of the following noun.

Subject pronouns:

- 1st person: jeg, veir

- 2nd person: tu, eir

- 3rd person masculine: hann, teir

- 3rd person feminine: hon, tær

- 3rd person neuter: tad, tau

I decided to keep the distinction between the third person plural pronouns because collapsing everything into neuter seemed to be a little boring.

Object pronouns:

- 1st person: mig, oss

- 2nd person: tig, ydur

- 3rd person masculine: honum, teim

- 3rd person feminine: hen, teim

- 3rd person neuter: tad, teim

Here, the third person plural is the same in all genders, which it how it was in Old Norse.

Possessive pronouns:

- 1st person singular: minn, min, mitt, minar

- 1st person plural: vaur, vaurt, vaurar

- 2nd person singular: tinn, tin, titt, tinar

- 2nd person plural: ydar, ydart, ydarar

- 3rd person masculine singular: hans, hansar

- 3rd person feminine singular: henar, henrar

- 3rd person neuter singular: tess, tessar

- 3rd person plural: teirra, teirrat, teirrar

Only the 1st and 2nd person singular possessives distinguish between the masculine & feminine genders on the following noun. The 3rd person singular possessives don't distinguish gender at all, just number.

Here are some examples with 1st person possessives:

- køttinn minn "my cat"

- boukin min "my book"

- augat min "my eye"

- armarnir minar "my arms"

- eidinn vaur "our oath"

- husit vaurt "our house"

- beinin vaurar "our bones"

The third person possessive pronouns do not specifically refer to the subject or speaker; they can refer to absolutely anyone. Like with the other North Germanic languages, there is a separate set of reflexive pronouns - sinn, sin, sitt, sinar - which are used to clear up ambiguity:

- køttinn henar "her cat"

- køttinn sinn "her (own) cat"

"It"

Like the other pronouns, the Askeisk word for "it" is declined for case, number, and gender. The "default" form is tad.

Adjectives

Like you'd expect, adjectives take on the case, number, and gender of the noun they modify. Adjectives with /a/, /u/, and /au/ in the masculine (the default form of the adjective) become /ø/, /y/, and /øy/ in the feminine.

Examples:

- daud, døyd, daudt "dead"

- fraul, frøyl, frault "free"

- heit, heit, heitt "hot"

- redd, redd, reddt "afraid"

Adjectives can "agree" with 1st and 2nd person pronouns by matching the gender of the person:

- Jeg em glad. "I (male) am happy."

- Jeg em glød. "I (female) am happy."

- Jeg em gladt. "I (neuter) am happy."

- Tu ert glad. "You (male) am happy."

For the plural versions of the 1st and 2nd person pronouns, the neuter forms of adjectives are used by default:

- Veir eru gladt. "We are happy"

- Eir eru gladt. "You are happy".

Since adjectives have the same declensions as nouns, gladt is the same in the singular and plural numbers.

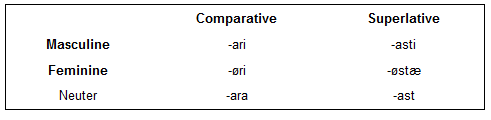

Comparatives & superlatives also have different forms depending on the gender of the adjective:

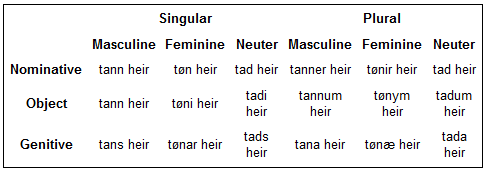

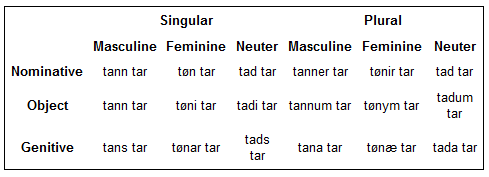

Determiners

Like in Swedish (and probably the other Scandinavian languages, but I don't know for sure since I've only studied Swedish), determiners are formed with a combination of tann "it" + heir/tar.

The proximal demonstratives "this/these" are:

And the distal demonstratives "that/those":

Examples

- Tann heir er køttrinn minn. "This is my cat."

- Tad tar epli eru raudt. "These apples are red."

- Tøn tar er døttrin sin. "That is her daughter.

- Tønir tar røydhakar eru smølær. "Those robins are small."

The Definite & Indefinite Articles

The definite article is suffixed to the noun. The indefinite article comes from the word einn meaning "one". It declines in the way any other noun does.

Verbs

Verbs are not nearly as complex as they are in Old Norse. I prefer to create highly regular conlangs, and there was a lot that was irregular in Old Norse. Still, this is supposed to be a naturalistic language, and natlangs have a lot of irregularity and redundancy built into them.

Verbs have four classes: strong, weak, preterite-present, and irregular. There is no subjunctive mood, primarily because I couldn't find enough examples of it on Wiktionary. That, and I didn't want to make more verb tables.

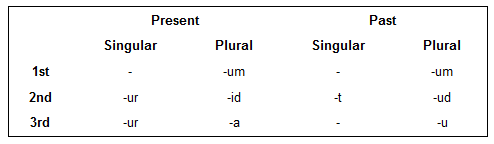

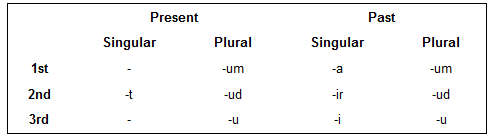

Verbs are marked for person (1st, 2nd, 3rd), number (singular, plural), tense (present, past), mood (indicative, imperative) and have infinitive, present & past participle forms.

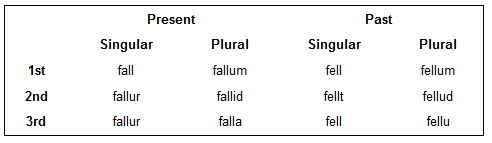

Strong Verbs

In strong verbs, the past tense and participle are indicated with a vowel change. This happens for every single vowel:

- /a/ → /e/

- /au/ → /ei/

- /æ/ → /ø/

- /ei/ → /øy/

- /i/ → /ei/

- /o/ → /a/

- /ou/ → /au/

- /ø/ → /y/

- /u/ → /au/

- /y/ → /ø/

The present participle ends in -andi, past participle ends in -inn, singular imperative is the stem, and plural imperative ends in -id.

Indicative verb endings are shown in the table below:

Example: at falla "to fall"

- Present participle: fallandi

- Past participle: fellinn

- Imperative singular: fall

- Imperative plural: fallid

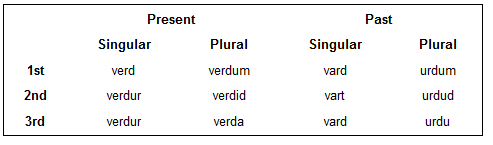

If a strong verb starts with the consonant /v/, then the first vowel in the past tense plural and past participle shift to /u/ while the initial /v/ is dropped.

Example: at verda "to become"

- Present participle: verdandi

- Past participle: urdinn

- Imperative singular: verd

- Imperative plural: verdid

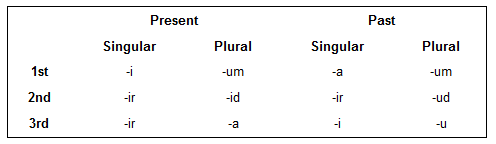

Weak Verbs

Weak verbs have no vowel shift, only verb endings to indicate tense and person.

The present participle ends in -andi, past participle ends in -dur or -tur, singular imperative is the stem, and plural imperative ends in -id.

Indicative verb endings are shown in the table below:

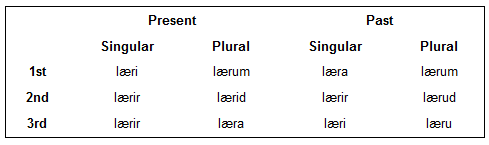

Example: at læra "to learn"

- Present participle: lærandi

- Past participle: lærdur

- Imperative singular: lær

- Imperative plural: lærid

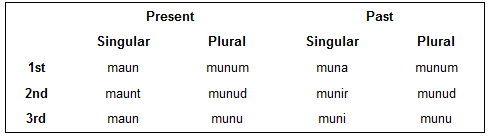

Preterite-Present Verbs

These are only a handful of verbs in this class, but they were interesting enough that I decided to keep them instead of putting them with the strong or weak verbs.

Present tenses are the same as strong verbs' past tenses, and past tenses are formed like weak verbs' past tenses. The participles are the same as weak verbs', the singular imperative is the stem, and the plural imperative ends in -ud.

Indicative verb endings are shown in the table below:

Example: at muna "to remember"

- Present participle: munandi

- Past participle: munadur

- Imperative singular: mun

- Imperative plural: munud

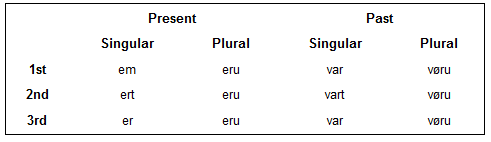

Irregular & Auxiliary Verbs

Askeisk only has a few irregular verbs. The most used is the copula, at vera "to be":

- Present participle: verandi

- Past participle: verit

- Imperative singular: ver

- Imperative plural: verid

Auxiliary verbs follow the same declension as weak verbs.

Passive Verbs

Passive verbs are formed by suffixing -sk to the verb form.

The Future Tense

Askeisk doesn't have a specific verb ending for the future tense. Most of the time, an auxiliary verb (munu, skulu, or vilja) is used in front of the bare infinitive form of the following verb.

Jeg munu fulgja tig. "I will (in the future) follow you."

Jeg skulu fylgja tig. "I will (must) follow you."

Jeg vilja fylgja tig. "I will (intend to) follow you."

A temporal adverb can be used with a present tense verb to indicate that an action occurs in the future:

Jeg fylgjir tig senn. "I'll follow you soon."

Negating Verbs

The adverb ekki "not" is used to negate verbs:

Jeg em ekki gladur. "I am not happy."

Tau er ekki fornt. "They are not old."

The Present & Past Perfects

The weak verb hava "to hold" can be used as an auxiliary verb when the following verb is in its supine form. The supine form is formed by suffixing the verb stem with -(a)t.

Jeg havi fylgjat tig. "I have followed you."

Jeg hava fylgjat tig. "I had followed you."

The three points below are what I’ve decided to focus on for the time being. I am hoping that sticking to them will keep me on track with my writing, instead of being sidetracked with conlanging.

1. If there is more than one conlang present, those conlangs should be easily distinguishable.

The most obvious way to distinguish a conlang from another – especially a naming language – is visually. What’s your orthography going to be like? What letter(s) are you going to use to represent a single phoneme? What about diphthongs or affricates? Vowel length? Syllable stress?

Latin indicates long vowels with macrons (ā ē ī ō ū), while Finnish doubles the letter (aa ää ee ii oo öö uu yy). French uses <ch> to represent /ʃ/, which English uses <sh> and Nahuatl uses <x>.

What about syllable structure? Does your conlang allow consonant clusters? English does – strengths /stɹɛŋkθs/ has three at the beginning of the syllable and four at the end – while languages like Japanese and Hawaiian don’t really permit any.

This means I’d never have any conlangs that are as similar as Spanish and Italian – or Spanish and Portuguese. Unless, of course, the similarity is the point and both conlangs are part of the same language family. But even then, I ensure that those conlangs can be easily visually distinguished.

2. The conlang should be easy for the author to type.

Once upon a time (2012), I wrote a novel with names that included the letter š. I don’t have a keyboard that can type š by default. Even changing my keyboard layout to US-International (which I have used for over a decade at this point) did not allow me to type š. I had to either copy-paste it (in both upper and lowercase form) or turn on Number Lock and type Alt+0154. It was annoying.

You might want your conlang to have a specific aesthetic; I know I usually do. But ask yourself this: is it worth being annoyed while you’re writing it? If you can handle that, go ahead and use š or any other difficult-to-type letters. If you can’t, you ought to look into changing your orthography a little. Or getting a new keyboard.

3. Do the minimum amount of work possible.

First, you’ll need to identify just how much of the conlang you want in your story. Are you exclusively using the conlang to name things? Do you plan on writing full passages in it? Once you’ve made a decision, do just enough work to accomplish that goal. That means strictly sticking to creating a naming language and nothing more if all you need is names. There’s no reason to flesh out the grammar even if you really want to. That takes up time that can be spent on other things, like actually writing your story.

At the time of writing this, I have not actively been into conlanging since late 2021. I can’t pinpoint an exact date or even a reason – it certainly wasn’t because of a lack of free time, that’s for certain – but it was a hobby that I had slowly begun to accept that I would probably never get back into. I hadn’t had any particular “reason” to conlang (not that I ever needed any reason before), not even for my stories. I skipped Lexember in 2023 and 2022. I was completely disconnected from any conlanging communities.

When I realized that I didn’t want to use English nature words as character names in my current story project, I was not looking forward to the obvious alternative – creating a shiny new conlang. I was so out of practice that I did not know if I would even be able to create a naming language – which, in hindsight, is pretty ridiculous since I wrote an entire guide on how to create one. It was my most popular post on Wordpress for years. For a while, it was on the first page of Google for the search “naming language”. That’s how well-received it was.

I’ve only worked on this new conlang for a couple of days, but things have gone very well so far. In fact, I would go so far as to say that it has been easy – much easier than I expected it to be, especially since I had zero plans going in. I didn’t know what phonemes I wanted to use, or what orthography, and that’s typically something I have in mind before I start work on a conlang. But the point is that it’s been easy, not difficult.

I really thought that my conlanging days were over, and that I’d never be able to make one again. Thankfully, I was wrong. I should also point out that I thought the same about art – that I might not be able to get back into it – and I was wrong there as well.

This has actually done a lot to soothe some of my own worries about getting back into old hobbies I haven’t practiced in a while – and starting new hobbies entirely. So long as I have interest and put in a little effort, things should turn out fine.

Posted to Dreamwidth on 27 November 2024, backdated to 12 November 2021. Originally posted on Wordpress.

Introduction

Zarya Heul is a conlang I originally created in 2015. I'd been reading about the Tocharian languages and was inspired, so Zaryaheul /zarja.heɯl/ took some influences from Tocharian and was intended to be spoken by a fictional Central Asian people. It had some extreme vowel harmony (syllables could only contain front vowels or back vowels, not both) and consonant assimilation, which I thought was impressive at the time but probably contributed to me losing interest in the conlang after a few months.

When it came time to write The Book of Immortality, I decided to revamp Zarya Heul. I dropped the vowel harmony, greatly simplified the consonant structure, and decided that words wouldn't compound/stick together like they previously did. This brought it from a somewhat synthetic language to a more analytic one.

Information relevant to The Book of Immortality:

Zarya Heul "silk language" is a language spoken in the homelands of the Zarya Tel people. These homelands comprise the entirety of the West Zarya Wa Province and the majority of East Zarya Wa Province in the Meitsung Empire, as well as some lands to the north and west of the Empire.

Phonology

Zarya Heul's consonant inventory is fairly "normal". The 2015 version of the conlang had voiced and unvoiced versions of each consonant (not just stops), but that was dropped in the final version.

- Nasals: m n ŋ

- Stops: p b t d k g

- Fricatives: s z h

- Affricates: ts dz

- Approximants: l j w

- Trills: r

- Close: i u

- Mid: e o

- Open: a

Syllable structure is CVN, where:

- C = any consonant

- V = any vowel

- N = any voiceless alveolar, /n/, and /ŋ/

Stress usually falls on the first syllable. Words are rarely longer than three syllables.

Nouns

All modifiers (adjectives, numbers, etc.) precede nouns and case markers follow. Nouns are not inflected as Zarya Heul is an analytic language. The resulting "noun phrase" is NUMBER ADJECTIVE NOUN CASE.

There are six numbers: singular, dual, general plural, small plural, large plural, and all. As the singular is default, it is unmarked.

- Dual: et

- General plural: as

- Small plural: wo

- Large plural: vi

- All: apa

Examples:

- kin astar mawu "one black cat"

- men kiye gung et "two red houses"

Nouns have multiple case markers: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, and instrumental.

- Nominative: -

- Accusative: len

- Genitive: sil

- Dative: ra

- Instrumental: neng

- Ablative: din

- Allative: ku

- Adessive: gat

- Inessive: hera

- Elative: long

- Illative: yo

Pronouns

Pronouns are treated the same as nouns; they are preceded by modifiers and followed by case markers.

| Person | Singular | Gen. Plural |

| 1st | yel | as vel |

| 2nd | sen | as sen |

| 3rd | daru | as daru |

Reflexive pronouns are followed by the marker nar:

| Person | Singular | Gen. Plural |

| 1st | yel nar | as vel nar |

| 2nd | sen nar | as sen nar |

| 3rd | daru nar | as daru nar |

Verbs

Verbs have two types of markers: auxiliaries which express modality, and tense. Auxiliaries precede the verb and tenses follow it. If the verb is negated, the negation particle is first in line.

There are five tenses: far past, near past, present, near future, and far future.

- Far past: esa

- Near past: arza

- Present: toku

- Near future: ker

- Far future: lau

The far past is used for actions that happened a significantly long time ago. What is considered a long time is fairly flexible, and usually up to the speaker.

Yel weki esa zarya heul len.

- I spoke Zarya Heul a long time ago.

- 1SG speak FAR-PAST zarya heul ACC

The near past tense is used for actions that happened recently. It is similar to a perfect aspect.

Yel woan arza as kisang len.

- I recently saw snakes.

- 1SG see NEAR-PAST GEN-PL snake ACC

The present tense is only used for actions that are currently occurring.

Yel miya toku.

- I’m running right now.

- 1SG run PRES

The near future tense is used for actions that will happen soon. Like with the far past, what is considered "soon" is up to the speaker.

Yel penke ker as sare len.

- I will buy eggs soon.

- 1SG buy NEAR-FUT GEN-PL egg ACC

The far future tense is used for actions that will happen far in the future.

Yel penke lau as sare len.

- I will buy eggs at some point.

- 1SG buy FAR-FUT GEN-PL egg ACC

Verbs that are not marked for tense can be used for general statements:

Yel miya.

- I run (for exercise, as a hobby, in general, etc.).

- 1SG run

Yel penke as sare len.

- I buy eggs.

- 1SG buy GEN-PL egg ACC

Verbal auxiliaries are used in place of mood:

- Can/could: dur

- May/might: king

- Must/shall: tenai

Dur is used to indicate that an action can be carried out:

Yel dur miya.

- I can run (I am capable of running).

- 1SG can run

King is used to express that an action could possibly occur:

Yel king penke as sare len.

- I might buy eggs.

- 1SG might buy GEN-PL egg ACC

Tenai is used to express that a verb is an obligation or requirement:

Yel tenai penke as sare len.

- I have to buy eggs.

- 1SG must buy GEN-PL egg ACC

Negation is indicated with the particle tu:

Yel tu miya toku.

- I’m not running right now.

- 1SG not run PRES

Other Parts of Speech

Zarya Heul has two determiners: ngas "this", which is used for objects close by, and keyu "that", which is used by objects further away.

There are two locative adverbs: poku “here” and tsung “there”. Location can also be expressed with the constructions ngas kilar “this place/here” and keyu kilar “that place/there”.

Zarya Heul has multiple question words. Interrogative phrases start with a question word and end with the question tag mat:

- How: lang

- What: garas

- When: muka

- Where: liya

- Why: yar

- Who: tuwe

- Question tag: mat

Examples:

Yar sen miya toku mat?

- Why are you running right now?

- Why 2SG run PRES question-tag

Liya sen penke as sare len mat?

- Where do you buy eggs?

- Where 2SG buy GEN-PL egg ACC question-tag

Posted to Dreamwidth on 26 November 2024, backdated to 8 November 2021. Originally posted on Wordpress.

Introduction

Of the conlangs I created for the the story that eventually became The Book of Immortality, the dragon language was always the most fleshed out. It had to be, as it was used as a magic language and there were going to be passages written in it. I didn't have to expand the grammar much.

Also, this conlang didn't have a real name until earlier this year. Célis zisun means "mountain language", and it's one of the two dragon languages spoken in Greater Meitsung - primarily in East and West Rhécare. The other dragon language, mízha zisun "island language", is spoken on the island of Mízharos.

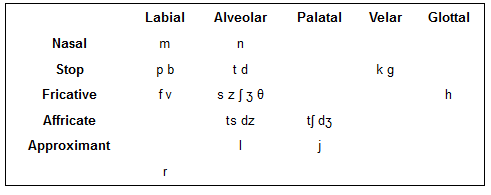

Phonology

The original dragon language contained /ɲ/, /ɸ/, /β/, /x/, /ɣ, and /ʍ/ in addition to every consonant listed in the table below. The number of fricatives was truly ridiculous, and it made no sense to have /ɸ β/ and /f v/ as well as /h/ and /x/. Those consonants weren't even allophones or anything - they were independent phonemes.

- Nasals: m (ɱ) n

- Stops: p t d k g

- Fricatives: f v θ ð s z ʃ ʒ h

- Approximants: l j w

- Rhotics: ɾ r

- Close: ɪ i u

- Mid: ɛ e o

- Open: a

Diphthongs are /iu/, /io/, /iɛ/, and /ia/. Syllable structure is CVF, where C is any consonant, V is any vowel, and F is /n/, /l/ or /s/. There are no words that start with vowels. Primary stress falls on the first syllable of a word, and secondary stress falls on following odd syllables.

Orthography

Since this conlang was first developed when I was still obsessed with Irish orthograph, there are some influences - namely, using <c>to represent /k/. That also immediately distinguishes it from the other languages of Meitsung.

| Letter | a | c | d | dh | e | é | f |

| Sound | /a/ | /k/ | /d/ | /ð/ | /ɛ/ | /e/ | /f/ |

| Letter | g | h | i | í | l | m | n |

| Sound | /g/ | /h/ | /ɪ/ | /i/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ |

| Letter | o | p | r | rh | s | sh | t |

| Sound | /o/ | /p/ | /ɾ/ | /r/ | /s/ | /ʃ/ | /t/ |

| Letter | th | u | v | w | y | z | zh |

| Sound | /θ/ | /u/ | /v/ | /w/ | /j/ | /z/ | /ð/ |

Nouns

Nouns (and adjectives) are marked for case, number, and definiteness; those markers are suffixed in the form case-number-definiteness with the exception of the vocative case, which is a prefix.

There are six cases: nominative, genitive, accusative, dative, instrumental, and vocative. For some strange reason, there were originally separate possessive and genitive cases. I'm genuinely not sure why.

- Nominative: -Ø

- Genitive: -in

- Accusative: -ul

- Dative: -eta

- Instrumental: -we

- Vocative: a-

Célis zisun has two numbers: singular and plural. The singular is unmarked, and the plural suffix is -le. Nouns are assumed to be indefinite by default. The definite ending is -(a)ne.

Why is there even a definite marker in this conlang? I'm not sure. Perhaps I was thinking of the Scandinavian languages at the time.

Pronouns

Pronouns are marked for case and number in the same way nouns are - not definiteness, because...that wouldn't make any sense.

- 1st singular: len

- 1st plural: riv

- 2nd informal singular: rhal

- 2nd informal plural: rhale

- 3rd singular: dhas

- 3rd plural: dhasle

Verbs

Verbs are marked for tense, mood, and person/number. There are three tenses: past, present, future, and three moods: indicative, subjunctive, and imperative. The 2nd person formal and informal are not distinguished in verbs.

Numerals

Célis zisun's number system is base ten. To form numbers in the teens, the word lemu "ten" is followed by a numeral. For example, lemu fari is 15. To form multiples of ten, a numeral (2, 3, 4, etc.) is followed by the plural form of ten. Heda lemule is 40 and pel lemule wora is 68.

Other Things

There is a copula, hen, that's much more irregular than other verbs. Adjectives follow nouns, and adverbs follow verbs. Word order is Subject-Object-Verb, and has been through all forms of this conlang.

Despite this conlang being more fleshed out than the previous two, it's still largely a naming language. Perhaps sometime in the future I'll come back and work on it more, but for now this is all there is.

Posted to Dreamwidth on 25 November 2024, backdated to 1 November 2021. Originally posted on Wordpress.

Introduction

In the very first, 2014 version of The Book of Immortality, there were five languages, four of which descended from a single proto-language.

The four languages descended from the proto-language were separated into two families: dragon and tiger. The dragon languages were the language of patience (an ancient language, akin to Latin, which was used in the modern day for casting magic spells by dragons and elves) and the river tongue, which was the modern language spoken by the dragons (akin to the modern Romance languages). The tiger languages were the language of passion (again, an ancient language akin to Latin, used in the modern day for magic exclusively by the tigers) and the white language, the modern tiger language.

The fifth language was "Common", spoken by elves and humans. It was represented by English.

Once The Book of Immortality reached its current form, I revamped the dragon and tiger languages and also created a conlang for the humans and elves: meitsung soré. The dragon language is much more fleshed out and requires a blog post of its own, but the tiger language and meitsung soré are fairly basic naming languages.

Mayu Lháni

Mayu lháni literally means "tiger language". It always contained /ɬ/, but the uvular consonants were added in the final version of the conlang.

- Nasals: m n (ɴ)

- Stops: p b t d k g q

- Fricatives: s ɬ x (χ)

- Approximants: r l j w

- Close: i i: u u:

- Open: a a:

Syllable structure is CVC. Mayu lháni is agglutinative, and word order is Verb-Subject-Object. Since I never actually fleshed out anything other than nouns, this doesn't matter much.

Nouns have four cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative) and three numbers (singular, dual, plural).

| Case | Singular | Dual | Plural |

| Nominative | - | -pe | -ma |

| Accusative | -ge | -pege | -mage |

| Genitive | -a | -pea | -má |

| Dative | ih | -peih | -maih |

I also created some numbers:

- 1: tús

- 2: pín

- 3: har

- 4: qina

- 5: nálhi

- 6: ísa

- 7: wara

- 8: lhuyu

- 9: táki

- 10: kata

- 100: talhi

- 1000: qin

Meitsung soré

Meitsung soré means "splendid language". Since I knew from the beginning that all I needed was a naming language, all I created was the phonology and orthography. There's no actual grammar in this conlang.

I spent some time wondering if I wanted to have both /r/ and /l/. I ended up liking enough of the words with /r/ in them that I kept them both.

- Nasals: m n ŋ

- Stops: p t k

- Fricatives: s ɕ h

- Affricates: t͡s t͡ɕ

- Approximants: ɹ~ɻ l j w

- Close: i u

- Mid: e (ə) o

- Open-mid: ɛ

- Open: a

Introduction

Ciniáne or Ciniáthyssyn "Ciniá's language" is the language of the Ciniáne people. Prior to the Cataclysm, it was the most-spoken and official language of Ciniáthyleruggeá, The God-Republic of Ciniá. In the present day, it is spoken by most of the Ciniáne, an ethnic minority group of Tsurennupaiva.

Ciniáne was created in December 2016 for the second version of The Gate at the End of the World. The God-Republic of Ciniá was the country that Brithan Thiosciáre was from. I imported the character, country, ethnic group, and language into The Land of Two Moons.

Ciniáne's phonology is influenced quite a bit by Greek & Italian. Ciniá itself was inspired by Mediterranean cultures, so the influences seemed appropriate.

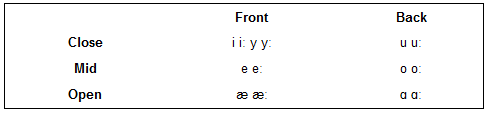

Phonology

All consonants can be geminated, though in practice this does not happen. Certain consonants "palatalize" before front vowels:

- /s/, /z/, /ts/, /dz/ → [ʃ], [ʒ], [tʃ], [dʒ]

- /kk/, /gg/ → [ttʃ], [ddʒ]

All vowels have long and short forms. Like with a lot of Romance languages (and perhaps other languages I am unfamiliar with), /i/ becomes /j/ before vowels.

Why does this Italian-looking language have /y/, /æ/, and /ɑ/? Well, I'd just learned about Finnish vowels at the time, and I wanted a more symmetrical phonology. I also wanted to be able to use in the alphabet.

Ciniáne also has a couple of dipthongs: /ɑi/, /æi/, /ei/, and /ou/.

Syllable structure is CVC, where C is any consonant (including geminated consonants) and V is any vowel (including diphthongs). I genuinely do not know why I did not flesh this out further.

Word stress is...inconsistent. Stress falls on the syllable with a long vowel, wherever that syllable might be. In words where there is no long vowel, stress falls on the penultimate syllable.

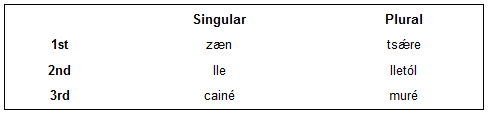

Pronouns

Pronouns are marked for case in the same way nouns are.

Ciniáne is pretty different than most of my other conlangs regarding pronouns...because the plural forms aren't simply the singular with the plural suffix. That is genuinely what I do most of the time.

Nouns

Nouns have three cases: nominative (unmarked), genitive (-thy), and dative (-sú). The nominative is used in most places, the genitive is used to show possession and that a noun modifies another noun in some way, and the dative is used when the noun is any kind of object.

Nouns have two numbers: singular and plural. The plural marker is -tól.

- béll "star" → bélltól "stars"

- cithæ "person" → cithætól "people"

- ssyn "language" → ssyntól "languages"

Adjectives

Adjectives precede nouns, and are not marked in any way.

- eníane mǽlury "beautiful illumination"

- gellæne lemúre "blue sky"

- teleraí leccýne "exalted god"

To create adjectives from nouns and verbs, the suffix -ne is used. Most adjectives are created this way, even ones like that would like "blue" and "green" - there are Ciniáne nouns for "blue thing" and "green thing", and they have -ne suffixed to created the adjectival versions of those words.

Ciniáne, by itself, means "of or pertaining to Ciniá". Ciniáthyssyn is the specific word for the language, and Ciniáthycithætol is the word used to refer to the ethnic group.

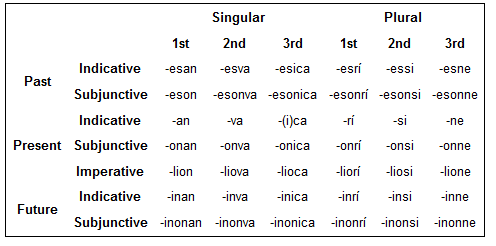

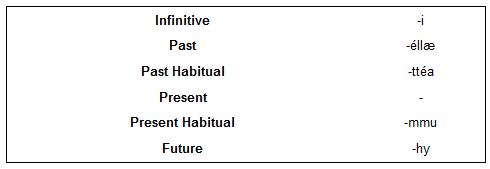

Verbs

Verbs are marked for tense and aspect:

I never created a large dictionary for Ciniáne. Here are some example sentences showing the different verb forms, using hyvælli "to speak":

Zæn hyvæll Ciniánesú.

- I speak Ciniáne.

- 1SG.NOM speak.PRS Ciniáne.DAT

Tsǽre hyvællmmu Ciniánesú.

- We (from time to time) speak Ciniáne.

- 1PL.NOM speak.PRS.HAB Ciniáne.DAT

Lle hyvælléllæ Ciniánesú.

- You spoke Ciniáne.

- 2SG.NOM speak.PST Ciniáne.DAT

Cainé hyvællttéa Ciniánesú.

- He/She/Ze used to speak Ciniáne.

- 3SG.NOM speak.PST.HAB Ciniáne.DAT

Muré hyvællhy Ciniánesú.

- They will speak Ciniáne.

- 3SG.PL speak.FUT Ciniáne.DAT

Concluding Thoughts

Ciniáne is essentially a glorified naming language. When I created it in December 2016, it was so I had a conlang to participate in Lexember with. After I stopped working on The Gate at the End of the World, I had no real reason to work on the conlang anymore, so I abandoned it. Even after moving it over to The Land of Two Moons, it remained untouched.

I doubt I'll come back to this conlang again. I still have no reason to touch it! However, Ciniáne is still phonologically & orthographically interesting to me, so I imagine I'll recycle some parts of it into another conlang someday.

Posted to Dreamwidth on 24 November 2024, backdated to 19 July 2021. Originally posted on Wordpress.

Introduction

Fèdzéyí is one of my older conlangs. It was created in 2015, and the original ideas for the conlang are very different than how it turned out.

The then-unnamed conlang was one of three languages in a language family, all three of which were spoken by a fictional people who lived in and around a canyon. At that point, there were some influences from Romanian, of all languages. I'd already decided that the language structure would resemble Japanese (CVN syllables), but with tones.

At this point, I decided that the original idea for the conlang needed to be scrapped. I scrapped the language family idea entirely and decided to take inspiration from Mandarin & Navajo, two languages I was looking into at the time. I had a very poor understanding of both of those languages, and it showed.

Eventually, Fèdzéyí moved away from those influences and became something of its own. Fèdzéyí means "circle language". When I named it, I still had the idea of making it be spoken by a fictional group of people. After some time, I abandoned that entirely and kept the name.

Fèdzéyí is primarily based on verbs. All verbs have a "base" form that is monosyllabic, with grammatical particles attaching to them. Most nouns are derived from verbs with an accompanying class suffix. There are very few "true" adjectives; most of the time, verbs are used in their place as descriptors.

Phonology

Fèdzéyí has a syllable structure of CVN, where:

- C = any consonant or /kw/

- V = any vowel

- N = /n/ or /ŋ/

/m/ was originally included as a final, but I dropped that when I realized that would create too many base words.

Consonant inventory:

- Nasals: /m/, /n/, /ŋ/

- Stops: /p/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, /g/

- Fricatives: /f/, /v/, /s/, /z/, /ɕ/, /ʑ/, /h/

- Affricates: /tɕ/, /dʑ/

- Approximants: /l/, /j/, /w/

- Trills: /r/

I spent some time deliberating on whether I wanted a voicing or aspiration distinction on the stops, and also whether or not I wanted to include /f/ and /v/, and whether I wanted to delete /r/ entirely and only have /l/.

Vowel inventory:

- Front: /i/, /u/

- Central: /ə/, /a/

- Back: /u/, /o/

There was originally a distinction between long and short vowels, but again, it created too many base words.

Fèdzéyí has three tones: level, rising, and falling. The rising tone is indicated with an acute accent, and the falling tone is indicated with a grave accent.

Verb Construction

A verb is constructed in the form Modifier-Adverb-Stem-Mood-Tense.

"Modifiers" are particles that indicate positivity (vùn) or negativity/negation (éng). You can use verb with vùn prefixed to indicate that you completed an action (such as if you were asked if you already took out the trash). Éng is used in largely the same way.

Adverbs are just verb stems that are used to modify the main verb. There's nothing particularly unique about them.

Fèdzéyí has four moods: indicative (keun), subjunctive (dzo), conditional (rà), and imperative (hì). The three tenses are past (heu), present (da), and future (dzí).

I once considered marking person and number on the verbs since the conlang is so verb-heavy to begin with, but decided against it as it would make the words too long for my own liking.

Noun Construction

This is where things get fun.

The vast majority of nouns are based on verb stems. They're constructed in the form Determiner-Verb Stem-Class-Number/Numeral-Case-Adjective.

There are proximal, medial, and distal determiners. They're either singular or plural, and this is a bit redundant with the numeral being marked elsewhere, but you know what? Redundancy is a part of most (all?) natural languages, so I have no problem putting it into this conlang.

- Proximal: dà, dàho

- Medial: tú, túho

- Distal: néng, néngho

There are ten noun classes, and they're used to create nouns out of verb stems:

- People: wu

- Animals: lu

- Plants: ò

- Heavenly objects, weather: é

- Body parts: neu

- Human-made objects (tools): mùng

- Vehicles, methods of transport: ngèù

- Human-made inanimate objects: kwí

- Naturally-occurring inanimate objects: ye

- Abstract inanimate concepts: dzé

Let's look at the name of the language, Fèdzéyí:

- fè = verb, to enclose/encircle

- dzé = noun class, an abstract inanimate concept

- yí = noun, a language

Fè+dzé creates the noun "circle". Yí is one of the few nouns that isn't based on a verb, and means "language".

(Since there's a word for "encircle", I decided to create verbs for other shapes - en-rectangle, en-triangle (èn), en-square, en-parallelogram - because why not?)

Let's look at a couple more nouns I've created:

- do "to gift " + kwí "human-made inanimate object" = dokwí "a gift"

- fo "to swim"+ vàng "to be scaly" + lu "animal" = fovànglu "fish"

- mi "to meow + lu "animal" = milu "cat"

- nè "to count" + dzé "abstract concept" = nèdzé "number"

- ngí to fly" + ngèù "vehicle" = ngíngèù "airplane"

- shé "to flow" + é "heavenly object" = shéé "water"

- tsà "to know" + dzé "abstract concept" = tsàdzé "knowledge"

There are a couple of numbers: singular (not marked), "some" (meun), a general plural (ho), and a mass plural (kún). If an exact number is needed, you can just put a numeral in that slot instead.

There aren't as many cases in Fèdzéyí as in some of my other conlangs, primarily because...I didn't want to deal with very many. That's the whole reason.

Fèdzéyí cases:

- Nominative: unmarked

- Genitive: ú

- Accusative: shí

- Dative: vé

- Instrumental: yún

- Locative: vi

- Adessive: ní

- Inessive: dzu

Like adverbs, adjectives are verb stems that are used to modify the noun.

Sentence Structure

Naturally, word order is Verb-Subject-Object. Due to the number of cases, it can actually be more flexible than that, but there's really no reason to use anything other than VSO.

If the sentence is a question, then the question word comes at the beginning of the sentence. Question words are:

- dèn - when, at what time

- eng - who, what person

- gè - what

- gè nèdzé - how many

- kí - why

- úng - where, at what place

- yu - a generic question word that's used when none of the others apply

Following are examples of each question word:

Dèn lódzodzí waho?

- When do we leave?

Eng tú?

- Who is that?

Eng ténkeunda milushí?

- Who owns the cat?

Gè tú?

- What is that?

Gè nèdzé zhekeunda ingho wínkwídzu?

- How many people are in the house?

Kí éngdzekeunda ngóho?

- Why aren't you sleeping?

Úng zhekeunda ngó?

- Where are you?

Yu túlu milushí?

- Is that (animal) a cat?

Background & Introduction

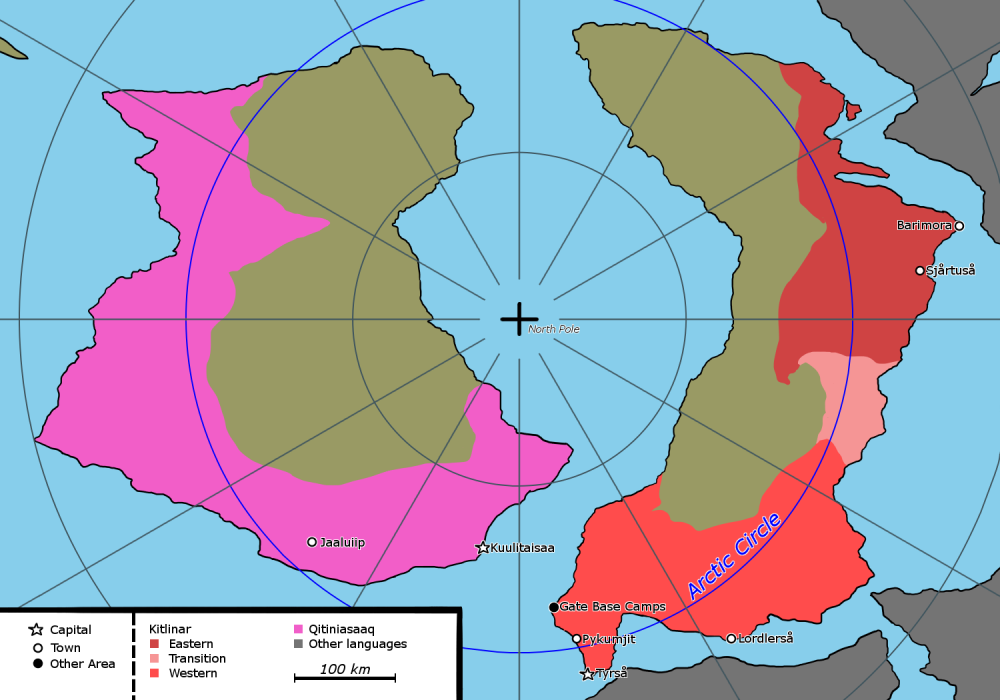

I created Qitiniasaaq in 2016, sometime after I'd created Kitlinar. It's less complete than Kitlinar, since the first version of The Gate at the End of the World only had one Qitiniina character and the Qitiniasaaq language wasn't spoken.

I never bothered creating any specific dialects for it like I did with Kitlinar, even though it'd likely have many more dialects. I guess what I'm describing here is the Kuulitaisaa dialect.

You may have assumed that this language has some phonological and orthographical influences from the Inuit languages, and you'd be correct. It also has some inspirations from Finnish - primarily in the number of cases it has.

Consonants

[ɴ] is an allophone of /n/ and only occurs at the end of words.

- Nasals: m n ŋ (ɴ)

- Stops: p t k q

- Fricative: s

- Approximant: l j

Vowels

Vowels are either long or short. Diphthongs are the same.

- Close: i iː u uː

- Open: a aː

Syllable Structure and Stress

Syllable structure is CVC, where:

- C = any consonant

- V = any vowel or diphthong

The majority of syllables are CV, with CVC syllables mainly occurring word-finally.

Primary stress usually falls on syllables with long vowels.

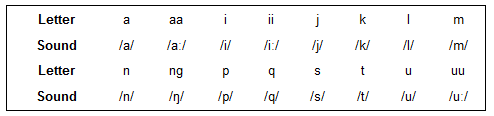

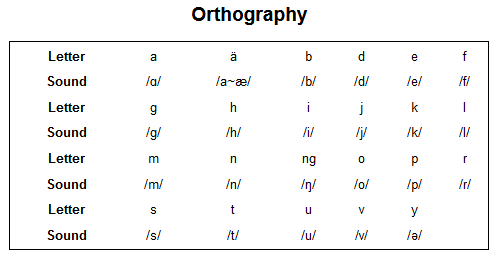

Orthography

Pronouns

Qitiniasaaq didn't even have any pronouns until I started cleaning up all my notes a couple of months ago. That's how little grammar I made for this language - it's basically a glorified naming language!

As a result, the pronoun system is fairly standard and boring:

- 1st person: liin, liinik

- 2nd person: sana, sanamik

- 3rd person: main, mainik

Nouns

Nouns are marked for case & number. They can also take on a demonstrative determiner as an interfix. Adjectives are fused onto the end of the noun, and any noun can be used as an adjective without any modification - til can mean both "ice" and "icy".

Short phrases formed with the genitive case tend to become one word, such as qitiniasaaq "tundra's language". This is broken down into qitin "tundra" + ia "genitive" + saaq "language".

Qitiniasaaq is also ergative-absolutive instead of nominative-accusative like most of my languages - another major influence from the Inuit languages.

- Ergative: -kaa, -kaamik

- Absolutive: -Ø, -(m)ik

- Genitive: -ia, -iamik

- Dative: -inuu, inuumik

- Comitative: -pi, -pimik

- Instrumental: -qui, quimik

- Abessive: -miu, miumik

- Ablative: -tau, -taumik

- Allative: -kaai, -kaaimik

- Adessive: -laa, -laamik

- Inessive: -qu, -qumik

- Elative: -sau, -saumik

- Illative: -naa, -naamik

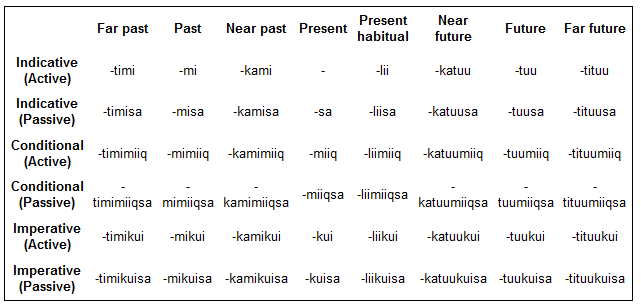

Verbs

Verbs are declined for tense, mood, and voice. They aren't declined for person, but pronouns can be stuck onto the end of the verb.

- Tenses: far past, past, near past, present, present habitual, near future, future, far future

- Moods: indicative, conditional, imperative

- Voice: active, passive

I think Qitiniasaaq is the first language where I made a distinction between near & far past/future tenses. That's something I've used in other conlangs I've created since 2016.

Not all conjugations in the table below exist - I haven't yet figured out which ones don't:

Here's an example of the passive/active voice:

Kaalaliiliin Qitiniasaaq.

- I speak Qitiniasaaq.

- speak.PRS-HAB.IND.ACT.1SG Qitiniasaaq.ABS

Kaalaliisaliin Qitiniasaaq.

- Qitiniasaaq is spoken by me.

- speak.PRS-HAB.IND.PASS.1SG Qitiniasaaq.ABS

Resemblance to the Greenlandic Inuit word "kalaallisut" is entirely coincidental. Seriously!

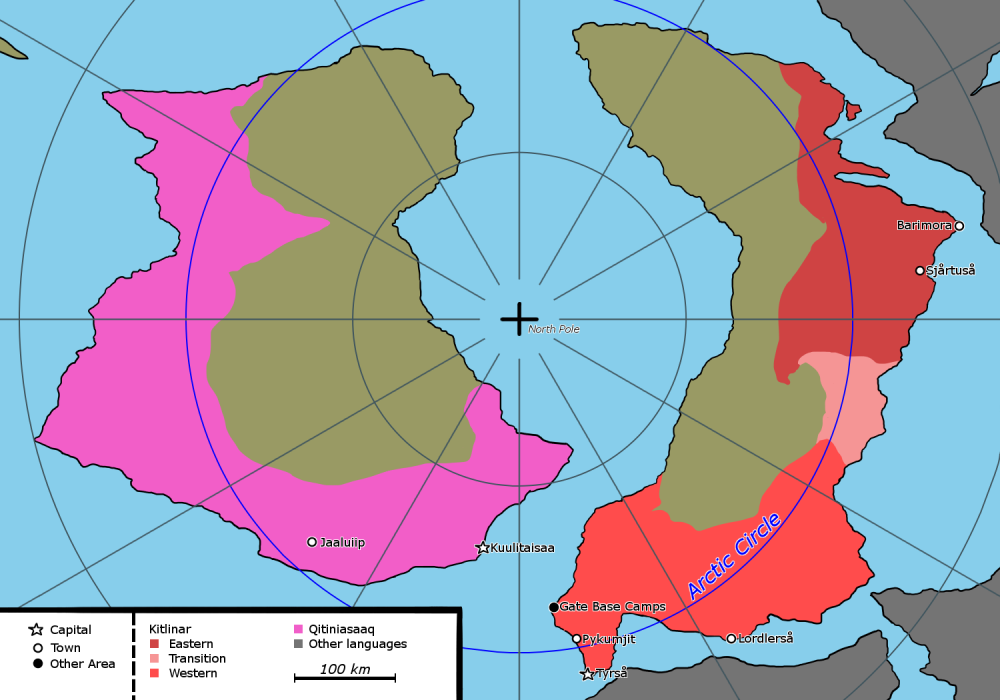

Background & Introduction

Kitlinar is a language I created in 2016 when I was developing the first version of The Gate at the End of the World. While that version of the story never ended up working out, the conlangs and worldbuilding were something I decided to keep.

Kitlinar is a language spoken on the eastern parts and islands of the land of Kitlin (called Qitin by the Qitiniina). It has been spoken in Kitlin since before recorded history. It is a language isolate and its origins are unknown, though the language was likely brought to Kitlin by its speakers, who are unrelated to the indigenous Qitiniina. Kitlinar has many loanwords and some grammatical influence from Qitiniasaaq, the language spoken by the Qitiniina.

There are two main dialects: eastern and western. Eastern dialects use retroflex consonants in place of the /rC/ consonant clusters used in the western dialects; this is seen in the pronunciation of the capital city Tyrsä: [ˈtə.ʂæ] vs. [ˈtər.sa]. These retroflex consonants did not exist in Kitlinar before it split into the two dialects.

The phonology of Kitlinar was primarily inspired by the Swedish & Norwegian languages. Before I reformed the orthography, it used <å> instead of <ä> to represent /æ/. You can see this in the old map up above; I only have a png version and can't change the text.

Consonants

With the exception of /j/, the palatal consonants are allophones of /Cj/ clusters in the Western dialects. In the Eastern dialects, they are independent phonemes.

Retroflex consonants are allophones of /rC/ clusters in transition dialects, while they are independent phonemes in Eastern dialects.

- Nasals: m n ɳ ɲ ŋ

- Stops: p b t d ʈ ɖ c ɟ k g

- Fricatives: f v s ʂ ɕ ç h

- Approximants: l ɭ j

- Trills: r

Vowels

/a/ is usually /æ/ in Eastern dialects.

Eastern Kitlinar has a couple of diphthongs, gained from /Vl/ & /Vj/ shifting to /Vu/ and /Vi/. Western Kitlinar has no diphthongs, and transition dialects vary.

- Close: i u

- Mid: e ə o

- Open: a~æ ɑ

Syllable Structure & Stress

Syllable structure is (C1)V(C2), where:

- C1 = any consonant or initial consonant cluster

- V = any vowel

- C2 = any consonant or final consonant cluster

Initial consonant clusters are CA & CT, while final consonant clusters are AC & AT, where:

- C = any consonant

- A = any approximant

- T = /r/

Primary stress falls on the initial syllable. Monosyllables are unstressed.

Orthography

Pronouns

Pronouns are marked for case and number. The third person distinguishes animacy.

The first person singular and plural are unique words, while the plurals of the 2nd and 3rd persons just take on the plural.

- 1st person: jer, lun

- 2nd person: mird, mirdyt

- 3rd person animate: alt, altyt

- 3rd person inanimate: häj, häjt

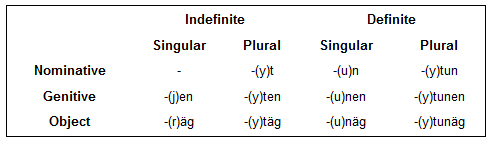

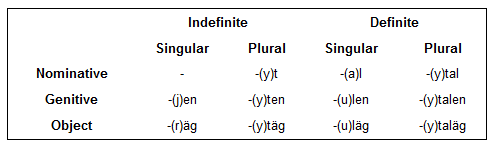

Nouns & Adjectives

Nouns are either animate or inanimate and are marked for case, number, and definiteness. Plants, animals, humans, and things like weather and volcanoes are animate, while things that do not or never move are inanimate. This is distinguished only through the definite suffix; case and number are marked in the same way on animate and inanimate nouns.

There are three cases: nominative, genitive, and object. The object case covers direct and indirect objects of verbs; in that manner, it's essentially a combined dative/accusative case.

Adjectives precede nouns and take on the case, number, and definiteness of the noun.

Animate nouns:

Inanimate nouns:

Verbs

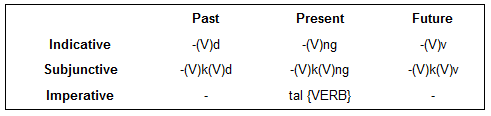

Verbs are conjugated for mood and tense.

- Moods: indicative, subjunctive, imperative

- Tenses: past, present, future

The future tense is used exclusively with the subjunctive mood:

Alt hyrvekev mar jartitun girnekev.

- Ey will change when the glaciers melt (stubborn people do not change their minds easily).

- 3SG.ANIM change.SBJ.FUT when glacier.PL.DEF.NOM melt.SBJ.FUT

The imperative mood is used for commands; the verb stem is preceded by word tal:

Tal bart lunäg!

- Help us!

- IMP help we.OBJ

I know the past and present tenses look pretty similar to English's (-d for past tense verbs and -ng for present tense) but I genuinely was not thinking of that when I was creating the tenses, and I don't particularly feel like changing it, either.

Forming Factual Statements

Kitlinar has no copula; in places where English would use one for statements of existence or fact, Kitlinar uses a "factual statement" particle, lirs:

Lirs fjevud häj.

- It is special.

- FS special 3SG.INAM

Additional Sentences

Jer herdekev loj parunäg.

- I'll travel to the sea.

- 1SG.NOM travel.SBJ.FUT toward sea.DEF.OBJ

Frujen frujeng ben rad.

- The sun shines warmly.

- Sun.NOM.DEF shine.IND.PRS with warm

Slenyt kjul altäg.

- Blessings of the goddess on you (pleased to meet you).

- Blessing.NOM.PL on 3SG.ANIM.ACC